Links

Sheba Medical Centre

Melanie Phillips

Shariah Finance Watch

Australian Islamist Monitor - MultiFaith

West Australian Friends of Israel

Why Israel is at war

Lozowick Blog

NeoZionoid The NeoZionoiZeoN blog

Blank pages of the age

Silent Runnings

Jewish Issues watchdog

Discover more about Israel advocacy

Zionists the creation of Israel

Dissecting the Left

Paula says

Perspectives on Israel - Zionists

Zionism & Israel Information Center

Zionism educational seminars

Christian dhimmitude

Forum on Mideast

Israel Blog - documents terror war against Israelis

Zionism on the web

RECOMMENDED: newsback News discussion community

RSS Feed software from CarP

International law, Arab-Israeli conflict

Think-Israel

The Big Lies

Shmloozing with terrorists

IDF ON YOUTUBE

Israel's contributions to the world

MEMRI

Mark Durie Blog

The latest good news from Israel...new inventions, cures, advances.

support defenders of Israel

The Gaza War 2014

The 2014 Gaza Conflict Factual and Legal Aspects

To get maximum benefit from the ICJS website Register now. Select the topics which interest you.

Netanyahu fights for political survival

Israeli prime minister struggles to rally the public to his side after Oct. 7 attacks

Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu issued a rare apology Sunday that inadvertently framed the political crisis that has engulfed him.

A few hours earlier, facing mounting criticism for the Hamas attacks that killed 1,400 Israelis, he publicly blamed the security failures on Israel’s defence and intelligence services. He hadn’t been warned of Hamas’s intention to start a war, he wrote in a tweet on X, saying that defence and intelligence officials had “assessed that Hamas was deterred.” Soon after, he deleted the tweet and apologised.

The unusual reversal illustrates Netanyahu’s increasingly fraught position. Over 35 years in politics, he has cultivated an image as a security hawk tough on Palestinian violence and ready to face down the threat of a nuclear Iran. That image shattered Oct. 7 when more than a thousand Hamas militants entered Israel in what many Israelis are calling the worst security and intelligence failure in its 75-year history.

Now he faces a maddening balancing act that requires him to explain the country’s security failures; mount a war with Hamas in the Gaza Strip; seek to return hostages held by the Islamist group; and keep his coalition together amid growing criticism for the Oct. 7 attacks. Even if Israel wins the war, it may not save his political career.

Unlike many wartime leaders, Netanyahu is struggling to rally the public to his side. Israelis have blamed him in eulogies for the dead; his ministers have been shouted out of hospitals and pictures have been published of red paint smeared on the headquarters of his Likud party to look like blood.

Members of Likud who spoke with The Wall Street Journal avoided publicly criticising the prime minister, saying the country needed to focus first on defeating Hamas before a post-mortem on what went wrong and who was to blame for Oct. 7.

One senior Likud official said Netanyahu’s fate depends on how the war with Hamas plays out, but he is unlikely to survive as leader of the party, and thus as prime minister.

It is “the end of the game for him,” the official said. “You would find very few people who would say differently.” Asked at a press conference Monday whether he had considered resigning because of the drop in his support since the Oct. 7 attack, Netanyahu said, “The only thing that I intend to have resigned is Hamas. We’re going to resign them to the dustbin of history … This is my responsibility now. And it’s something that I think unites the entire country.” Netanyahu’s decadeslong approach to Hamas is now under particular scrutiny.

In response to Netanyahu’s tweet Sunday, his far-right coalition partner, Itamar Ben-Gvir, wrote on X that the failure for the attacks wasn’t a miscommunication in the run up, but an “entire misconception” over containing Hamas.

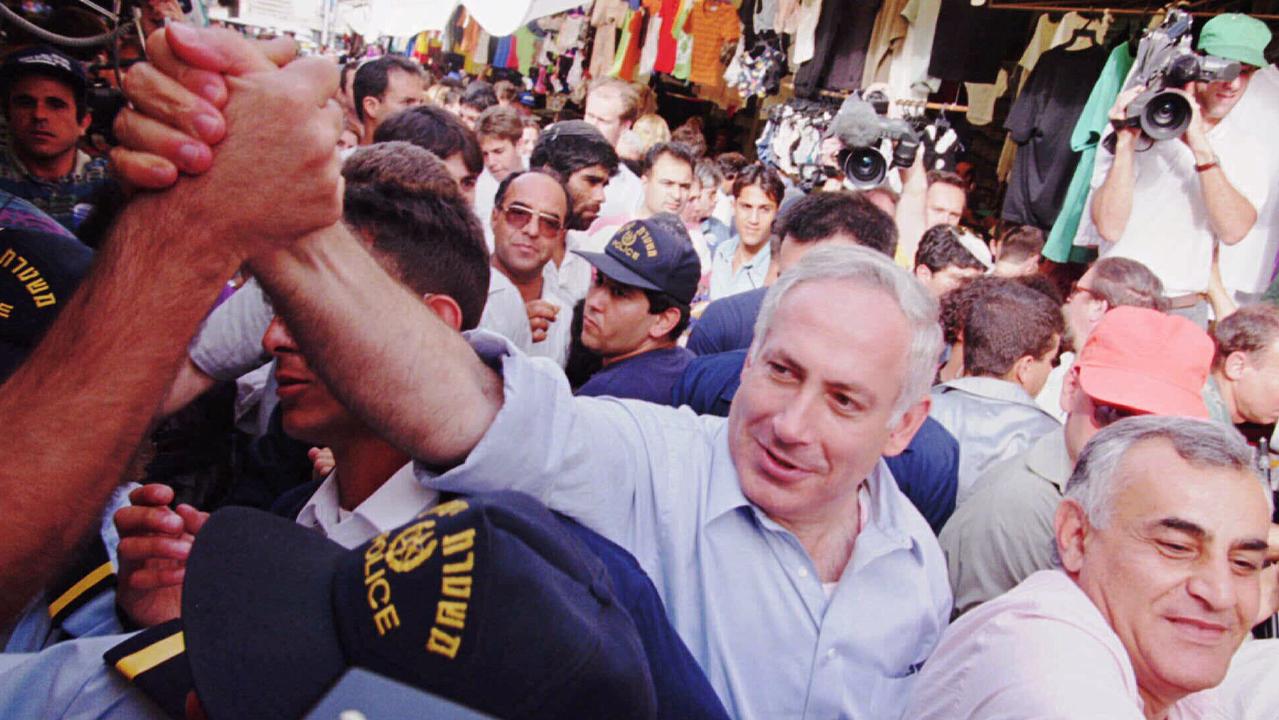

The Hamas calculation Netanyahu first became prime minister in 1996, serving only one term, before winning re-election in 2009 on a mandate to tackle security challenges and the economy. Hamas two years earlier had wrested control of Gaza from the internationally-recognised Palestinian Authority and Netanyahu was presented with the challenge of managing what Israel considered a terrorist organisation in its own backyard.

In opposition, Netanyahu had warned publicly that Gaza would become “Hamastan” under the direction of Iran. But when he became prime minister, he chose not to go into the Palestinian enclave with soldiers to disarm the group.

While some members of Israel’s security establishment pushed to demilitarise Hamas, Netanyahu opted to follow a strategy of allowing Hamas to govern in Gaza and remain armed while attempting to deter it from violence, according to Uzi Arad, Israel’s national security adviser under Netanyahu from 2009 to 2011.

The policy continued even as Israel fought tit-for-tat conflicts with Hamas in Gaza. In the biggest flare up between the two sides in 2014, Israel sent troops into Gaza to destroy a tunnel network created by Hamas to attack Israel, but the government refrained from a broader ground offensive to take down the group.

The security establishment largely backed the policy to contain Hamas. But Netanyahu also was willing to allow Hamas to arm and rule Gaza, Israeli political experts said, because it divided the Palestinian leadership between the strip and the West Bank, controlled by the Palestinian Authority.

That made a peace deal in which Israel was forced to give up parts of the West Bank unlikely, which appeased his right-wing coalition partners who opposed such an outcome, some political analysts said.

Security officials “constantly spoke of the need to strengthen the more moderate Palestinian Authority … strengthen them at the expense of Hamas, ” said Yohanan Plesner, president of the Israel Democracy Institute, a Jerusalem-based think tank.

But, he said, Netanyahu saw “it as quite a desirable outcome to have two separate political entities representing the Palestinian people.” In public statements, Netanyahu has said the Palestinian Authority, led by President Mahmoud Abbas, can’t be considered a partner for peace because while it recognises Israel, it doesn’t recognise Israel as the home for the Jewish people, and hasn’t engaged constructively in peace negotiations. The Palestinian leadership says Netanyahu adds conditions aimed at obstructing peace negotiations.

Political comeback Starting in 2019, Netanyahu appeared more focused on repeated rounds of elections than tackling Hamas. No Israeli political party could get enough votes to dominate parliament, leading to a year-long stalemate.

For a moment, it appeared Netanyahu’s career was finished. He faced a trial on corruption charges — which he denied — and was pushed out of government in 2021 by a disparate coalition of parties that agreed on little except they wanted Netanyahu out. It proved an unpopular basis for governing and at the end of last year, Israel voted in its fifth elections in four years.

Netanyahu again emerged victorious, but only after pulling together a coalition ultranationalist and religious parties with a majority of 64 in a 120-seat parliament. They focused the government and army resources on protecting Jewish settlers in the West Bank and pushed for highly controversial reform of the judicial system.

Hundreds of thousands of Israelis protested the moves, threatening to refuse to serve as reservists in the army and prompting intervention by the military.

“Netanyahu has been a beleaguered leader for the last two to three years, ” said Arad, who has turned into a vocal critic of his former boss. “He survived and even won elections, but it was done against a massive movement of protest … weakening his position.” On the eve of the Oct. 7 attacks, the outlook looked brighter for Netanyahu. He’d successfully pursued a policy of seeking to establish diplomatic relationships with Arab nations, in part, he said, to marginalise the Palestinians and put pressure on them to accept a future peace agreement with Israel.

Ahead of a Netanyahu speech at the United Nations General Assembly in New York on Sept. 22, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman indicated his country — the biggest Arab economy and home of Islam’s holiest places — was moving toward establishing ties with Israel.

“Look at what happens when we make peace between Saudi Arabia and Israel, the whole Middle East changes,” Netanyahu said holding a map. “We bring the possibility of prosperity and peace to this entire region.” October 7 On the morning of Oct. 7, as Palestinian militants rampaged through the south of Israel, butchering Israeli citizens, Netanyahu was notably silent for a few hours. At midday, he issued a video statement, wearing a suit and white shirt, saying Israel was “at war.” Later that day, he met with the leader of the opposition, Yesh Atid’s Yair Lapid, about establishing a national unity government of mainstream parties to guide the country through the conflict. Lapid said publicly he asked Netanyahu to remove his far-right partners from the coalition as a condition for creating a national unity government.

“Netanyahu said no, which means he’s already thinking about how he keeps this majority together for the day after the conflict,” said Reuven Hazan, in the political-science department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Netanyahu instead brought in Benny Gantz of the National Unity Party, who said he would join a government without forcing any party out.

Soon after the attacks, public anger against Netanyahu’s ministers erupted. “You’ve ruined this country! Get out of here!” a doctor shouted at the environmental protection minister Idit Silman outside a hospital, according to a video posted online.

Images appeared both online and in public spaces of Netanyahu’s face covered with a bloodied red hand, a replica of posters Ukrainians created of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s face.

Netanyahu visited troops mobilising for war, this time wearing a black shirt and body armour, rather than a pressed suit. When the Israeli leader met and took photos with the special forces unit, called Sayeret Matkal, that Netanyahu served in, some refused to stand as he walked out the room, despite orders from their officers to be respectful, according to a person in the unit On Oct. 14, he travelled to Kibbutz Be’eri, where authorities discovered more than 100 bodies, in a visit that angered residents who had already been evacuated and felt that he went to do a photo-op in their homes at their expense, said the community’s spokesman, Alon Pauker.

“Mr Prime Minister, go in front of the press and apologise for the thousands of people who were murdered on your watch,” Shirel Hogeg told a television station from a medical centre where his family members were being treated for burns after Hamas militants set ablaze their house.

Soon, the head of the Israeli military publicly took responsibility for the attacks. So, too, the internal security services chief and some of Netanyahu’s ministers. But the leader remained silent about responsibility for the security breach, despite being prime minister for roughly 13 of the past 14 years.

In a poll, four out of five Israelis said Netanyahu must acknowledge responsibility. A separate survey in Ma’ariv newspaper showed a collapse in the number of parliamentary seats Netanyahu’s Likud would win in an election, meaning it would be pushed from power should a vote be held now.

Tensions appeared between Netanyahu and his defence minister Yoav Gallant about how to respond to the attacks.

The two men made public statements individually, rather than together. Personal relations had been strained going into the war after Netanyahu fired Gallant in March over the defence minister’s opposition to the judicial overhaul on security grounds.

On Oct. 25, after days of public criticism for failing to take responsibility for the attacks, Netanyahu in a speech said that after the war, everyone will have to answer for failures, “including me.” Other prime ministers sacrificed their jobs in part because of major security blunders or failed wars, including Golda Meir following the surprise attack by Arab forces in 1973 and Menachem Begin in 1983 after a protracted conflict in Lebanon.

On Oct. 28, Netanyahu for the first time since the Oct. 7 attacks held a press conference and took questions, this time alongside Gallant and Gantz.

In the early hours of the next morning, he wrote his message on X that appeared to blame the security establishment for the failures.

Gantz asked the prime minister to retract the statement. Unusually, Netanyahu publicly apologised.

Ehud Yaari, a fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy and well-known Israeli political commentator, said Netanyahu would never take responsibility for the attacks and would instead try to take credit for a successful conflict with Hamas in order to remain in power.

“He’s totally dedicated — not just now, but for a while now — to his own political and personal survival,” Yaari said. “It’s going to get ugly.”

# reads: 2192

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu faces a maddening balancing act that requires him to explain the country’s security failures. Picture: Abir Sultan/Pool

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu faces a maddening balancing act that requires him to explain the country’s security failures. Picture: Abir Sultan/Pool  Israeli soldiers attend the funeral of a fellow soldier on November 1, 2023, in a military cemetery in Jerusalem amid the ongoing battles between Israel and the Palestinian group Hamas. Picture: Fadel Senna/AFP (Photo by FADEL SENNA / AFP)

Israeli soldiers attend the funeral of a fellow soldier on November 1, 2023, in a military cemetery in Jerusalem amid the ongoing battles between Israel and the Palestinian group Hamas. Picture: Fadel Senna/AFP (Photo by FADEL SENNA / AFP)  Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shakes the hand of a supporter while on a campaign-stop at Tel Aviv's Carmel Market May 14, 1996. Picture: Nati Harnik

Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shakes the hand of a supporter while on a campaign-stop at Tel Aviv's Carmel Market May 14, 1996. Picture: Nati Harnik  Palestinians evacuate a victim after an Israeli strike on a building in Khan Yunis in the southern Gaza Strip. Picture: Mahmud Hams/AFP

Palestinians evacuate a victim after an Israeli strike on a building in Khan Yunis in the southern Gaza Strip. Picture: Mahmud Hams/AFP  In September Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman indicated that his country was moving toward establishing ties with Israel. Picture: Bertrand Guay/AFP

In September Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman indicated that his country was moving toward establishing ties with Israel. Picture: Bertrand Guay/AFP  Mourners attend the funeral of husband and wife Meni and Ayelet, who were killed in the attacks on Kibbutz Be' eri on Oct 7. Picture: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

Mourners attend the funeral of husband and wife Meni and Ayelet, who were killed in the attacks on Kibbutz Be' eri on Oct 7. Picture: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images