Links

Sheba Medical Centre

Melanie Phillips

Shariah Finance Watch

Australian Islamist Monitor - MultiFaith

West Australian Friends of Israel

Why Israel is at war

Lozowick Blog

NeoZionoid The NeoZionoiZeoN blog

Blank pages of the age

Silent Runnings

Jewish Issues watchdog

Discover more about Israel advocacy

Zionists the creation of Israel

Dissecting the Left

Paula says

Perspectives on Israel - Zionists

Zionism & Israel Information Center

Zionism educational seminars

Christian dhimmitude

Forum on Mideast

Israel Blog - documents terror war against Israelis

Zionism on the web

RECOMMENDED: newsback News discussion community

RSS Feed software from CarP

International law, Arab-Israeli conflict

Think-Israel

The Big Lies

Shmloozing with terrorists

IDF ON YOUTUBE

Israel's contributions to the world

MEMRI

Mark Durie Blog

The latest good news from Israel...new inventions, cures, advances.

support defenders of Israel

The Gaza War 2014

The 2014 Gaza Conflict Factual and Legal Aspects

To get maximum benefit from the ICJS website Register now. Select the topics which interest you.

Israel’s stand against Iranian ambitions brings neighbours to the peace table

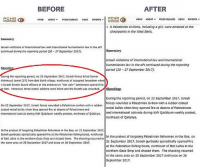

The White House has announced that Israel and the United Arab Emirates have agreed to sign a peace agreement in which the two nations will establish full diplomatic relations and “the exchange of ambassadors and co-operation on a broad range of areas, including tourism, education, healthcare, trade and security”.

The agreement is the most significant diplomatic development in the Middle East since Israel signed a peace treaty with Jordan in 1994 and it formalises a regional realignment that has been occurring clandestinely for decades.

It is difficult to overstate the historic nature of the agreement and its implications for the politics of the region. Since Israel declared independence in 1948 pursuant to the UN General Assembly partition plan to turn Palestine from a former Ottoman colonial possession into two nation-states, one Arab and one Jewish, a permanent state of war has existed between Israel and its Arab neighbours.

This has manifested in invasions of Israel in 1948, 1967 and 1973 by the combined armies of the Arab states on Israel’s borders, and endless skirmishes in the UN and international forums often to the discredit of those institutions and at the expense of far more pressing human rights and conflict issues.

This modus vivendi arose from an absolute rejection by the Arab world of Jewish claims to self-determination in any part of the land to which the Jews traced their origins and with which they maintained an unbroken physical connection for more than 3000 years.

The permanent state of war was formalised in an emergency session of the Arab League in Khartoum, Sudan, in the wake of Israel’s lightning victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, at which the member states agreed to what came to be known as the “three noes”: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel and no negotiations with Israel.

The UN offered a different path. Security Council Resolution 242 called for the cessation of war and conflict in the region through a mechanism known as “land for peace” by which the defeated Arab states would make peace with Israel in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from part or all of the territories Israel occupied in the 1967 war. This formula was successfully applied to reach landmark agreements with Egypt in 1979 and with Jordan in 1994.

Though Resolution 242 was intended to govern the relationship between sovereign states in the region and did not contemplate an Israeli agreement with the stateless Palestinians, the underlying principles of 242 — mutual recognition, territorial concessions and an end to war — were applied by the Palestinians and Israel in 1993.

US Ambassador to Israel David Friedman (2nd L), Senior Advisor Jared Kushner (2nd R), and US Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin (R) listen as US President Donald Trump announces an agreement between the United Arab Emirates and Israel to normalise diplomatic ties on August 13.

US Ambassador to Israel David Friedman (2nd L), Senior Advisor Jared Kushner (2nd R), and US Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin (R) listen as US President Donald Trump announces an agreement between the United Arab Emirates and Israel to normalise diplomatic ties on August 13.This resulted in the signing of the Oslo Accords, which led to multifaceted co-operation and the pursuit of a final status agreement to end the conflict.

But even while appearing to pursue its own bargain with Israel, the Palestinians demanded Arab solidarity against Israel through a strict doctrine of anti-normalisation — that is, Israel was to be treated as a pariah, an unwanted temporary interloper in the region of Islam and Arab nationalism, until it capitulated to Palestinian demands, including the settlement of up to seven million Palestinians in Israel, whose land area is roughly equivalent to Tasmania’s.

But while Arab leaders mouthed platitudes about solidarity against the Jewish state, the cartel of rejectionism and anti-normalisation was gradually being broken not only by the peace agreements but also by small though highly potent gestures.

In March 2018, Israeli passenger planes were permitted to fly over Saudi airspace for the first time. Later that year Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited the Omani capital, Muscat, while his sports minister flew to Abu Dhabi where Israel’s judo team was permitted to compete in a tournament, breaking a longstanding sports embargo. Netanyahu’s meeting with the Sudanese leader this year was particularly rich with symbolism given it was in the Sudanese capital that the anti-normalisation policy was adopted.

The process by which Arab nations have come to find peace with a sworn enemy is a remarkable one, a mix of power politics and pragmatism. For the Gulf states, Iran has long been the chief adversary, spawning tit-for-tat strikes and reprisals and enormous bloodletting through proxy wars in Yemen and Syria. The Sunni states were spooked by the Obama administration’s signing of the nuclear deal with Iran allowing it to salvage its economy, expand its weapons testing programs and deepen sponsorship of Hezbollah, the Assad regime and the Houthis.

For the Gulf states, seeing US and European leaders throwing their arms around the grinning Iranian foreign minister rather than exerting maximum pressure on the regime or, better still, facilitating its collapse left them feeling utterly exposed. They observed that the world leader most outspoken and fearless in opposing the Iran deal, and the only one who seemed to truly share their understanding of the brutal malevolence of the Iranian mullahs, was the Israeli Prime Minister.

Israel’s rapid transformation from a largely agrarian economy built on socialist ideals to supercharged capitalism from which new technology in medicine, cyber security and water management pours forth made the Jewish state harder to ignore, much less boycott. This has meant that world leaders now visit Israel less to hector on behalf of the Palestinians and more to sign agreements to transform their own economies and improve their citizens’ lives.

The self-defeating and baffling Palestinian approach of rejecting three offers of statehood since 2000 and now refusing even to negotiate to end the conflict with Israel has turned wider Arab fatigue with the Palestinian issue into exasperation bordering on apathy. The perpetual talk of the “Arab street” being alight with pro-Palestinian feeling has been proven hollow, enabling Arab leaders to make peace with Israel with no downside.

The decision of the UAE to find peace with Israel conceivably will pave the way for similar treaties with Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, further isolating the Iranian axis. It also will increase Israel’s regional integration and the fulfilment of the vision contained in its declaration of independence of achieving “peace and good neighbourliness” with the people of the region. This peace treaty has also revealed the realities of Middle East policymaking, vindicating Netanyahu in his long-held belief that peace comes through strength and economic utility, not simply by pleading with one’s adversaries for acceptance.

Alex Ryvchin is co-chief executive of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry and the author of Zionism: The Concise History.

# reads: 1251

Original piece is https://www.theaustralian.com.au/inquirer/israels-stand-against-iranian-ambitions-brings-neighbours-to-the-peace-table/news-story/68fa41fb73a5d0229b351568f2c62e6e