Links

Sheba Medical Centre

Melanie Phillips

Shariah Finance Watch

Australian Islamist Monitor - MultiFaith

West Australian Friends of Israel

Why Israel is at war

Lozowick Blog

NeoZionoid The NeoZionoiZeoN blog

Blank pages of the age

Silent Runnings

Jewish Issues watchdog

Discover more about Israel advocacy

Zionists the creation of Israel

Dissecting the Left

Paula says

Perspectives on Israel - Zionists

Zionism & Israel Information Center

Zionism educational seminars

Christian dhimmitude

Forum on Mideast

Israel Blog - documents terror war against Israelis

Zionism on the web

RECOMMENDED: newsback News discussion community

RSS Feed software from CarP

International law, Arab-Israeli conflict

Think-Israel

The Big Lies

Shmloozing with terrorists

IDF ON YOUTUBE

Israel's contributions to the world

MEMRI

Mark Durie Blog

The latest good news from Israel...new inventions, cures, advances.

support defenders of Israel

The Gaza War 2014

The 2014 Gaza Conflict Factual and Legal Aspects

To get maximum benefit from the ICJS website Register now. Select the topics which interest you.

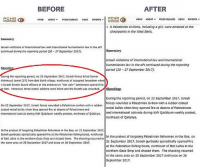

Islamophobia: reality or myth

Andrew West: The United Nations General Assembly gets under way in New York this week. Sometime during this session there’ll be a push by the 57 member countries of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation to make blasphemy an international criminal offence. Now this has long been a goal for many Muslim countries. But it’s got new impetus after an amateur film mocking the Muslim prophet Muhammad was posted on the internet. Since then a French satirical newspaper has also published some cartoons that depict Muhammad as naked. And in Australia some serving and former soldiers have posted anti-Muslim comments on a website.

The response from the worldwide Islamic community to all these events has ranged from violent, even deadly protests, to a Pakistani government minister offering a bounty for the death of the film maker, to the more general charge of Islamophobia. But is Islamophobia a reality or a myth? One expert says the term has been used to silence debate about Islam. Indeed writing in The Australiannewspaper recently, Clive Kessler called it a moral bludgeon. Clive Kessler is Emeritus Professor at the University of New South Wales. He’s an expert in the sociology of religion. He’s spent 40 years studying Islam, especially in Asia and specifically in Malaysia and he challenges the idea that Islamophobia is rife.

Clive Kessler: I think we have to look at the term itself. A phobia is an unfounded irrational baseless fear. The term Islamophobia is all too often used by zealous defenders of Islam as they understand it to silence the voicing of views that are uncongenial and unwelcome to them. And we cannot I think, have a situation where the term Islamophobia is used as a silencing device.

Andrew West: Well I think you’ve said in The Australian that it’s a moral bludgeon.

Clive Kessler: Well that’s what I mean by an attempt to silence people and silence the proper public discussions of issues. But let me take it a step further. We have to recognise that we stand now at a point where the inheritors of a legacy of civilisational rivalry, I won’t say conflict of civilisation but civilisational rivalry, between the world of Christianity, Christendom, and the world of Islam, for a number of centuries, through the crusades, through the colonial period and since then, and there is a legacy of fear, mistrust on both sides. And those fears, that mistrust, those resentments, those anxieties must be acknowledged, must be dealt with rather than all discussion of them being silenced with this moral bludgeon.

Andrew West: Do you think though we often confuse Islam and Islamism—and a distinction has been drawn—do you recognise a distinction?

Clive Kessler: I do. Whatever Islam as a religion and a civilisation may be, we are now in a historical situation where after a century or two of the subordination of Islam, many Muslims in the post-colonial era have now come out and wish to reassert themselves in history, reassert Islam in history. Among some people that is a quite proper and properly conducted enterprise. But among some, the notion of Islam itself becomes ideologised, we might say, becomes a sacred cow, and many of the people who see themselves as simply rallying to the defence of Islam are promoting Islamism as a political agenda.

Andrew West: Is it the case Clive, that you can criticise a political agenda—so in a sense you can criticise Islamism as a political extension of the religion—but if you criticise the religion itself, that’s when people get, you know, very defensive and accuse you of Islamophobia? Is that the problem?

Clive Kessler: That is it, yes. And I do not wish to see any faith community maligned, impugned, publicly humiliated. Under a proper ethic of multiculturalism one doesn’t do that sort of thing. But at the same time we have to recognise that there are a number of difficulties, particularly in the relationships among the three Abrahamic faith communities—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—the dynamic of whose inter-relationships, not just as religions but as civilisations, have shaped the contours of much of modern world history. And we cannot deal with the history, to which we are heirs, unless we get back to understand some complicated things about all of those three faith communities as religions and the dynamics of their civilisational interaction.

Andrew West: Well your piece in The Australian, it’s very measured, I mean, you make the case that one must come to this debate with clean hands, but that’s impossible isn’t it?

Clive Kessler: To be specific about this, let me say that Judaism emerged in the world conceiving of itself simply as monotheism. When Christianity came along it had built into it an attitude towards Judaism, that it was now the true Judaism and the first Judaism, the first dispensation was superseded. It has no inbuilt doctrinal view however of Islam. Islam came into the world self-consciously in its own understanding as the successor, the completion, the perfection of the Abrahamic faith, of the monotheistic revelation. And it has built into it, certain key attitudes towards Christianity—a scepticism towards the whole doctrine of the trinity, as to whether Christ died on the cross—and certainly a number of very decided views about Judaism, not so much born of doctrinal difference but born of the politics of inter-relationships between the community, the faith community of Muhammad and the Jews of Medina in the prophet’s lifetime.

Andrew West: Yes. You make the very strong point in this article that the Islamic writings are indeed infused with a quite dark view of history at times.

Clive Kessler: There is a view built into Islam as a religion and into the civilisation born of it, that it is the completion of the Abrahamic faith, that all that is good in Christianity and Judaism lives on within Islam, perfected and uncontaminated and uncorrupted. That which does not live on—that which Islam has not taken—is inherently erroneous, corrupted and to be repudiated. Now this then gets to the nub, I think the core, of much of the issue about Islamophobia. Many aspects of the civilisation of Islam become subjects of contention but none more so we know, ever since The Satanic Verses, than the status of the prophet Muhammad himself.

Andrew West: So why is that Clive?

Clive Kessler: The crucial thing about Islam is the status of the prophet Muhammad, that according to Islamic doctrine, the Koran is the divine, the word of God himself, that was then injected into the world through the medium of the prophet Muhammad and that is why any questioning of the prophet Muhammad calls into question the whole project of Islam itself.

Andrew West: Does the status of Muhammad, who was a warrior, does that in a sense, shape what are often considered to be warlike or very aggressive defences of him?

Clive Kessler: Certainly there is the notion that the reputation of the prophet must be protected. And certainly Islam came into the world as a success story. It came within a century of the prophet’s death to rule most of the known world. It lived in the world on its own terms. It wrote its own script. Now this was a very complicated process. Standard Islamic historiography says this was all done by…in peaceful ways that war and the sword were no major or key part of the whole project. So anyone who raises those questions about whether the spread of Islam was entirely peaceful is seen as impugning Islam and the prophet.

The problem for modern Muslims is, that for the last two or three hundred years, ever since Napoleon landed in Egypt, the civilisation of Islam has been in some sense a wounded, a violated civilisation that has not lived in the world on its own terms, but has had to live a historical script written by others, that has yearned to live in the world once more on its own terms and which in our present age is seeking to assert itself in that way.

So the consequence in places such as Australia in particular, outside the Middle East, is that Muslims are minorities living with a majoritarian complex born of the long history of Islam’s civilisational ascendency. And that means that many Muslims find it difficult to abide by any public criticism or comment about Islam or Muhammad that they find uncongenial. And that’s when the charge of Islamophobia is habitually raised.

Andrew West: Well in your article you say the term Islamophobia is used indiscriminately. But that implies there is occasionally or from time to time, a legitimate use of it. When would you say the term was used legitimately?

Clive Kessler: I don’t like the term Islamophobia in general but this does not mean to say that I think that Muslims do not have an entitlement to voice their sense of dignity and to say when they feel that the interfaith ethics of a multicultural society have been violated. And I think we all have to be sensitive to those concerns with all faith communities.

Andrew West: Do these protests that have broken out around the world, in the light of this comic film and now we’ve got a new batch of cartoons in a French newspaper—but these upsurges of anger occur periodically—do they suggest though, an immaturity in a reaction to a perceived insult of the faith?

Clive Kessler: They represent a quite, one might say, visceral, an understandably visceral response to the feeling that Islam has been impugned because the prophet Muhammad has been mocked. When I was a small boy growing up in a rather Jewish neighbourhood our local non-Jewish butchers always put pigs’ heads in the windows of the shops and stuck oranges or apples in the heads. And this was truly shocking to most Jews in the neighbourhood but they never said, look, out of deference to our sensitivities they shouldn’t put those pigs’ heads in the windows, after all 40 per cent of the people in this neighbourhood are Jewish. They said, look if we have a problem, that’s our problem; it’s not our society. And yet you’ll get exactly similar feelings both in Malaysia…in New York there was a recent case in Staten Island and even here where people will say, in our neighbourhood there are so many Muslims here, you shouldn’t be selling alcohol. Or you shouldn’t be selling pork chops. Why? Because to do so, is to confront us with something that we as Muslims find unpalatable or uncongenial and in some sense multicultural ethics require you not to do it. Now this is a case then, I would say, where similarly Muslims have to say, this is a problem of our sensitivities not of everybody’s. But the notion that the world must accommodate to those attitudes, among Muslims is, I think, very often a case of diasporic Muslims seeing the world and responding to things that do genuinely upset them. But responding to the problems of their minority situation through the prism, through the lens, of a majoritarian worldview that is the historic legacy of Islamic civilisation.

Andrew West: Well Clive Kessler, thank you very much for being on the program.

Clive Kessler: Pleasure.

Andrew West : And Clive Kessler is Emeritus Professor in Sociology at the University of New South Wales and an expert in Islam.

On the Religion and Ethics Report you’re with me, Andrew West.

# reads: 620

Original piece is http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/religionandethicsreport/islamophobia3a-reality-or-myth3f/4281896