There have been two major crises to confront the Secret Intelligence Service in the post-war era. The first came after 1951, when it was learnt that the KGB had successfully penetrated it at a senior level. Fifty years later, a second disaster struck – arguably more damaging in the long run – thanks to the free and easy relationship between MI6 and New Labour.

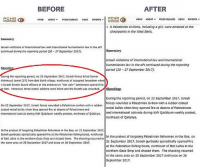

Tony Blair would talk publicly about intelligence briefings in a way that no prime minister had done before, making lurid claims about what he was being told by the intelligence services. Meanwhile, intelligence gathering lost its rigour, becoming partisan and politicised. The most shocking case remains the notorious dossier concerning Saddam Hussein’s so‑called weapons of mass destruction, presented to Parliament in September 2002, which turned out to be extremely badly sourced.

But it is still not widely understood that this disgraceful episode reflected a wider culture of slackness. I remember being taken aside by a New Labour spin doctor shortly after the 1997 general election, who told me that MI6 had been running an agent inside the Bundesbank.

The reason I was being vouchsafed this was nothing to do with national security. My informant was eager to damage the Conservative Party. The agent, I was told, had provided important details of the German negotiating position ahead of sterling’s eviction from the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. But the Conservative government had ignored this, making them even more stupid and culpable than was already the case.

On another occasion, in order to deflect attention from some ministerial scandal, the No 10 press office informed journalists that MI6 was investigating Chris Patten, now chairman of the BBC, for breach of the Official Secrets Act. This was completely untrue.

So last week’s sensational disclosure by Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair’s Downing Street chief of staff, that our spies used a fake rock filled with surveillance devices as a means of communication with their agents in Moscow (who the Russians claimed were posing as human rights campaigners) falls into a familiar pattern of New Labour indiscretion.

But Powell’s remarks, made in a four-part BBC documentary, Putin, Russia and the West, are a propaganda gift for Vladimir Putin. The Kremlin is determined to show that his critics are unpatriotic agents for the West. Powell’s indiscretion could not have been more helpful or better timed, just as the 2012 Russian presidential election campaign gets fully underway. He may have thought he was making an innocent, throwaway remark, but the brutal truth is that lapses like this can have deadly consequences.

Perhaps it is simply a coincidence that on January 19, the day that the BBC sent out a press release flagging up the comments, Alexander Kalashnikov, a senior figure in the FSB (the successor to the KGB), issued a vicious public attack on what he called “extremist organisations”, allegedly funded and directed from the West, which he accused of undermining Russia.

He named two of the most famous human rights organisations: Memorial (which honours the memory of victims of political terror during the Soviet era) and, more importantly, Golos, Russia’s only independent elections watchdog, which may play a key role in monitoring the presidential elections on March 4. Since then, Golos has been harassed, and threatened with eviction from its offices.

But it is certainly no coincidence that, three days after the BBC press release, a programme ran on prime-time Russian state TV, in which Powell’s indiscretion was used to make a full-frontal attack on some of the most respected independent critics of the regime.

The presenter, a Kremlin apologist called Arkady Mamontov, was clever. He exploited the fact that when the story about the rock first became public in 2006, many opponents of the regime were convinced by the official British denials that MI6 was involved. In particular, two of Putin’s most courageous critics, the radio presenter Yulia Latynina and the journalist Sergei Parkhomenko, were overtly sceptical of the Russian authorities’ accusations.

Now, thanks to Powell, their scepticism is being thrown back in their faces. One of Mamontov’s guests on the programme asserted that their claims to moral authority had been destroyed and that they were totally discredited.

Powell’s thoughtlessness is one thing. Of equal concern, however, is the documentary series in which Powell’s remarks appeared, the third part of which is screened tonight. This BBC series makes for utterly compelling current affairs television, is beautifully crafted and full of fresh and revealing testimony. I strongly advocate watching it.

However, on the basis of the two episodes which have appeared so far, there are grounds for doubting its balance. Even the blurb used to publicise the film suggests that the BBC has heavily bought into prime minister Putin’s own narrative: “How the great Soviet superpower, crushed and humiliated, has been resurrected in the form of Vladimir Putin’s new Russia.”

To Western viewers, brought up to look on Soviet Russia with hostility, this may seem a neutral and morally ambiguous description. But Putin could hardly have written a more glowing account of his achievements – particularly the implication that he has rescued Russia from being “crushed and humiliated”. There are important omissions from the film, and there has been no coverage of the Moscow apartment bombings of August 1999, which enabled Putin to make the case for the Second Chechen War and which were almost certainly carried out by the FSB. Furthermore, this Chechen conflict was an event of hideous brutality, bordering on a genocide: the BBC presents it as something closer to a routine counter-insurgency.

Of course, all films have to be selective, and the second film in the series struck me as much fairer than the first. Nevertheless, the overall narrative, I believe, is slanted towards Putin, a fact which becomes more disturbing when the identity of the main consultant to the series is taken into account.

Angus Roxburgh is well known to the British public as a former BBC Moscow correspondent. Much more relevant is the fact that Mr Roxburgh was a public relations consultant to the Kremlin for three years between 2006 and 2009. I have no doubt that he is a man of integrity, but it is profoundly shocking that the BBC should even have considered using him, given the nature of his previous employment.

Just imagine the outcry if the BBC were to employ President Ahmadinejad’s former spin consultant when making a film about Iran, or a former Tory central office type when making a film about David Cameron in a British election year.

So why is Roxburgh acceptable? I have been hearing very sad and alarming accounts about the BBC’s coverage of Putin’s Russia for over a decade. Those wanting to learn more can read an article written by the former BBC producer Masha Karp in Standpoint magazine in November 2010, which tells how her programme about the death of Alexander Litvinenko was suppressed by the World Service.

There are other such stories. As The Guardian correspondent Luke Harding records in his recent book, Mafia State, “the BBC Moscow bureau in particular is extremely reluctant to report on stories that might offend the Kremlin”.

The elections on March 4 are of huge importance. If he wins, Vladimir Putin can look forward to a further 12 years in power, making him the longest-serving Russian leader since Stalin. Some good judges believe that this outcome might plunge Russia into a new dark age. How fortunate for Putin that he has a useful idiot in Jonathan Powell and a fearful news organisation like the BBC to make life easy for him.