The recent best of the ICJS forum

This piece is reproduced from an article in The Age on 21st August 2004.

One minute, he's being dubbed the "Sheik of Hate" by the tabloids, the next, Taj El-Din Al Hilaly is inviting friends over for a barbie. So is our top-ranking Muslim an extremist, a misunderstood moderate or a menace to his own faithful? Richard Guilliatt investigates.

IT'S A WINTER THURSDAY MORNING IN Sydney's western suburbs, and Sheik Taj El-Din Al Hilaly has detected trouble among his Muslim flock. The Mufti of Australia is doing his rounds dressed in a style befitting his title -ankle-length royal-blue robe, leather sandals, gold-embroidered cream shawl and white Arabic turban - the biblical aura only slightly undermined by his chariot, a battered old Ford hatchback driven by his ubiquitous assistant, Keysar Trad. In the front passenger seat, Hilaly has a newspaper on his lap open to a news story revealing that Sheik Abdul Zoud, a rival imam who preaches at a prayer room near Hilaly's mosque in Lakemba, is trying to raise $2 million to buy a mosque of his own.

Finishing off his mobile telephone call, Hilaly points to the story and says something to Trad in Arabic. "The Mufti says these people are very destructive for multiculturalism," Trad translates. "He says if these people are allowed to open this mosque it will be bad for the community." Hilaly nods sagely, adding another comment. Trad continues, "He says, 'People will remember these words of mine after I die.'" At that moment, as if on cue, our car cruises past Malik Fahd High School, where on Christmas Eve 2000 Hilaly was attacked by an enraged mob of Sheik Zoud's followers. The incident ranks as one of the strangest and scariest of Hilaly's 22 years in Australia -which is no small claim when you consider he's also been stabbed, arrested, almost deported, denounced as an anti-Semite, charged with assault, thrown in an Egyptian jail for smuggling and attacked as an extremist by both Labor and Liberal governments. The mob numbered anywhere from 50 to 100, depending which eyewitness you talk to, and pummelled the Mufti's vehicle with sticks and iron bars. Hilaly, who was only three weeks away from his 60th birthday and had a heart condition which would shortly require a quadruple bypass, was nearly wrenched from the car and escaped only after the police turned up.

So it's no surprise to hear that Hilaly is not keen for Sheik Zoud's congregation to have a newly renovated mosque to gather in. Indeed, the Mufti's outspoken criticism of Islamic fundamentalists is often cited as the best evidence that he himself is no extremist, despite the many controversies his own sermons have sparked. It's Hilaly, after all, who is said to have banned Sheik Zoud and his followers from Sydney's Lakemba mosque, the largest Muslim congregation in the land, where the Mufti addresses an audience of thousands every week.

Yet nothing is ever quite so clear-cut in Sheik Taj Hilaly's world, where yesterday's enemy is today's ally and every spoken word contains many levels of meaning. So it's no surprise to hear that two weeks after our car ride, Sheik Zoud holds a fundraising dinner for his mosque, and there in the audience is Sheik Hilaly's representative, sent along to make a donation and encourage the faithful. When we next meet, I ask Hilaly why he contributed money to Sheik Zoud's mosque after predicting it would be bad for Australia. The Mufti pauses. He purses his lips. He frowns quizzically.

"Did I say that?"

LlKE MANY A STRIVING IMMIGRANT, SHEIK Taj Hilaly has enjoyed a measure of upward mobility since arriving in Australia in 1982. For nearly 20 years, he and his family occupied a modest fibro-and-concrete home next door to the Lakemba mosque, but now he splits his time between that house and a roomier brick duplex he and his son-in-law built in nearby Greenacre, a two-storey place with a double-width driveway, a covered back deck and a backyard prayer/meditation house. Hilaly shares one side of the duplex with his wife Souhair, son Mohammed and two youngest daughters; his 25-year-old daughter Shayma lives next door with her husband Ahmed, a surgical registrar at St George Hospital.

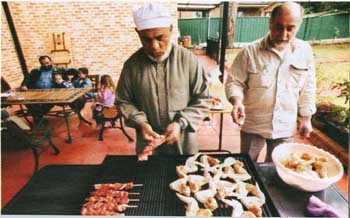

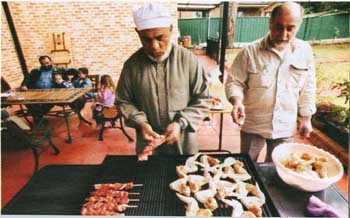

The place is so new it was still being worked on one recent Sunday afternoon, and one of the workers - a stocky, balding, brown-skinned bloke in green trackie daks and grey sweatshirt who was tipping rubbish into a wheelie bin - turned out to be the Mufti himself. Proffering his clean wrist in an adroitly courteous Muslim handshake, he explained he was tiling a backyard path before guests came over for an afternoon barbecue.

Away from the mosque, Hilaly is a keen home handyman and a fine cook, and his domestic life suggests anything but a religious fanatic. His daughters - Fatima, Asma and Shayma - are a trio of vibrant, dark-eyed twentysomethings who all have black belts in taekwondo, a sport their father insisted they pursue. Their 20-year-old brother Mohammed is considering a career as a policeman, a development that Hilaly - who was charged with assaulting a NSW police officer only last year - seems to find amusing.

"One day he might even oppose his father," he says, chuckling.

As even his detractors will tell you, Hilaly is a thorough charmer, with a quick wit and a strong, swarthy face that can switch from round-eyed innocence to earthy laughter at will. A backyard barbie chez Hilaly, with the

Mufti whipping up an aromatic feast of kebabs and marinated chicken while his wife and daughters hand out cans of Diet Pepsi, could be a postcard for migrant assimilation. "Any supermen here?" quips the patriarch, spooning out a fiery chilli mixture that drives several guests to coughing fits. The women eat separately, in deference to the presence of strangers, but later Hilaly's daughters gather around to chat about their father in broad Aussie accents. The "Sheik of Hate", as the tabloids have dubbed him, is in their eyes a "laid-back character" whose religious beliefs have always been moderate, and who was so keen for them to become Australians that he sent them all to the local public school, Beverly Hills High.

"It was heaps multicultural," enthuses 20-year-old Fatima, who plans a career as a financial planner. Shayma has a science degree, and nurtures an ambition to create her own line of herbal cosmetics, while 23-year-old Asma is finishing a business/law degree.

"But I don't want to be a criminal lawyer," she says with a rueful smile. "I've already spent most of my life defending myself and my family."

Indeed, Hilaly snr has required an awful lot of defending, most recently after a speech in Lebanon seven months ago which seemed to suggest that the September 11 terrorist attacks on the US weren't such a bad thing. Hilaly's sermons and pronouncements have been so inflammatory over the years that even the people who brought him to Australia in 1982 once lobbied to have him deported. For a man of the cloth, he's also been involved in an unusual amount of hand-to-hand combat: in the 1980s, he was twice charged with assaulting dissident worshippers outside the mosque, on one occasion shattering a mini-van window with a lump of wood (both cases were eventually dropped); a deranged man once x stabbed him in the face in an unprovoked street 5 assault; and early last year a routine traffic S matter with police - the Mufti had a piece of 3 aluminium cladding protruding from his car ended when he was handcuffed and charged with assault. Those charges were also dropped.

So when local Muslims marvel at his survival, they often mean the word literally. "With all these incidents that have happened to him, he never has a bodyguard," says one community leader incredulously. "Frankly, I would never want to be walking with him."

TO MAKE SENSE OF ALL THIS TUMULT, consider that Islamic Australia is a 450,000-strong community split into a bewildering array of factions. The cultural differences that separate Turks, Indonesians, Bosnians, Lebanese, Pakistanis, Fijians and north Africans are fractured further by theological differences between Sunni, Shiite, Sufi and other Islamic schools of thought. Deeper still are the sectarian rivalries between moderates and fundamentalists, Wahabi and Habashi, Bankstown and Brunswick. Many Australian Muslims outside Sydney have never accepted Hilaly as their leader, pointing out that a true mufti in the Middle East is a government-appointed Koranic scholar, whereas Hilaly's title is merely honorary, bestowed on him by the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils (AFIC), the highest Muslim body in Australia.

Mention Hilaly's name in the Muslim community and you will get wildly different opinions. Mohammad Mehio, manager of the Sydney radio station 2MFM, says bluntly that the Mufti is an extremist who was indelibly shaped by the radical Islam he was exposed to in Egypt, Libya and Lebanon. "He is not a moderate person - not politically, not Islamically, and not as a character," says Mehio "... He's almost like a streetfighter. It doesn't take long for the facade to come away and reveal his true colours." Yet Hilaly expelled the radicals of the Islamic Youth Movement from the Lakemba mosque in the late 1990s, and his supporters cite his family as evidence of how much he has embraced Australia.

Many secular Muslims, on the other hand, grumble that his failure to master English and his fierce denunciations of Western permissiveness reinforce Islam's reputation as an alien culture. "Sheik Taj's problem is his innate inability to understand Australian culture," says lawyer and community commentator Khaldoun Hajaj. "He hasn't really helped Muslim immigrants adjust to contemporary society. In private, his fear is that Arabs and Muslims will become more like Australians."

For his part, Hilaly often seems to be pouring fuel on the fire of these contradictions, creating a smokescreen of his own devising. In English-speaking forums, he has repeatedly denounced terrorism and repudiated suicide bombing, while his Arabic sermons praise Islamic martyrs in florid poetry. The laid-back suburban dad in Australia is also a fierce Islamic polemicist who's on friendly terms with Hexbollah leader Sheik I {assan Nasrallah; the' humble imam who survives on a $30,000 annual allowance is an inveterate overseas traveller who owns an apartment in Cairo and has dabbled in mysterious Egyptian property dealings.

Even people who have known Hilaly for years confess they can't pin him down. "I have heard him admire the Iranian government and I have heard him criticise them," says I )r Mohammad Tahir, a former secretary of AFK '.. "The problem is: which is the real Hilaly?'

Hilaly himself says he has always enjoyed "hot issues" more than day-to-day clerical duties such as marrying and advising the faithful, and his own history bears that out. Born in southern Egypt, he was a devoutly religious boy who memorised the Koran at 10 and undertook Islamic studies in Cairo, as his father and grandfather had done. As a young man he joined the Muslim Brotherhood, a radical group whose leaders had been executed in the 1950s after trying to assassinate President Nasser. The Brothers espoused a return to the old moral strictures of Islam, and their most radical thinker, Sayyid Qutb, is widely regarded as the founding theorist of violent jihad. But Hilaly says he fell out with Qutb's extremist followers.

"They took that school of thought to the extreme, militarily and religiously, condemning everyone as being infidel or heathen," he says, during an interview in his cluttered office at the Lakemba mosque. "And that was the worst mistake they made - it opened the door of evil for the movement."

By 1970 Hilaly was teaching Islamic studies

in Libya, where the 27-year-old army colonel Muammar Qaddafi had just staged a bloodless coup which deposed King Idris. Asked it he was politically active there, Hilaly offers a lopsided smile. "If there had been any movements, I might have joined," he replies, "but they were all in prison." By 1979, he had moved to the north of Lebanon, a country being ripped apart by civil war and Israel's invasion. Here, his fierce anti-Zionism was cemented - he still calls Zionists "the worst enemies of humanity" and his office is decorated with "Free Palestine" stickers.

Mohammad Mehio, who attended Hilaly's early sermons at the Lakemba mosque in 1982 and '83, says the Mufti's views arc-almost indistinguishable from those of radical groups such as Al Jamaa'al Islamya which flourished in Tripoli in the 1970s. "Listen to his speeches, his teachings, read the articles he puts in newspapers," says Mehio. "... A lot of his thoughts and teachings are of that -Al Jamaa'al Islamya."

Yet Nicola To'Meh, a Tripoli-based journalist for the Lebanese DailyStar and Agence France-Presse, says Hilaly is spoken of in the city as a moderate whose role was religious rather than political. And Hilaly himself sounds unequivocally opposed to extremism. "I really feel that the most dangerous thing for the youth is for them to adopt the sickness of extremist ideology," he says soberly. "There is unanimous thought among the scholars of Saudi Arabia that it is the ideology of outsiders to Islam."

"He hasn't helped Muslim immigrants adjust to contemporary society, in private, his fear is that Arabs and Muslims will become more like Australians."

HILALY HASNT ALWAYS SOUNDED SO conciliatory - his early sermons at Lakemba were fire-and-brimstone attacks not just on Israel and the West but also the corrupt Arab governments of the Middle East. Given that he was being paid partly by the Saudi government, via the Muslim World League, this created some heartburn at the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils. Mohammad Tahir recalls with a chuckle that some of the very AFIC officials who helped bring Hilaly to Australia in 1982 were, within a few years, lobbying the Hawke government to have him deported. Hilaly was only on a temporary visa at the time, and he didn't help his own cause when he gave a sermon in February 1985 -only a day after the government warned him to tone things down - that appeared to praise suicide bombers and denigrate non-Muslim society. The then immigration minister, Chris Hurford, instituted deportation proceedings a few months later.

But Hilaly showed he'd learned a thing or two about political manoeuvring during his years in the Middle East. First he sued the government, entangling the deportation in legal proceedings until Hurford had been moved on to other duties; then a palace coup within AFIC swept out his opponents and installed a pro-Hilaly executive. Meanwhile, his emissaries approached both the Hawke government and NSW's fragile Unsworth government to gently remind them of the importance of Muslim votes in the western suburbs of Sydney, where Labor was suffering a painful voter backlash. Three days before the 1987 federal election, Bob Hawke publicly hugged Hilaly at a Muslim community dinner attended by a who's who of the Labor Party, including the local member, Paul Keating.

One secret of Hilary's survival is the emotive power of his sermons, which still draw thousands every week to the Lakemba mosque. Even his detractors acknowledge he has no rivals in Australia as an Arabic orator -Mohammad Mehio recalls watching him whip his congregation into a fervor by proclaiming he would lock himself in the mosque rather than be taken away by the government. When AFIC bestowed the title of Mufti on him at its 1988 congress, Hilaly was elevated to a position of national religious leadership. Behind the scenes, many Muslims were furious, particularly outside Sydney. But AFIC continued to back Hilaly even after his infamous speech to Islamic students at Sydney University that same year, when he accused Jews of trying to control the world through "sex, then sexual perversion, then the promotion of espionage, treason and economic hoarding".

That speech ruptured his relations with the Jewish community, and Hilaly's protestations that he had been talking about Zionists rather than Jews earned him a reputation as a dissembler that has never really gone away. Paolo Totaro, the then head of the Ethnic Affairs Commission of NSW, recalls that three different translators all interpreted the speech the same way. Yet a year later, the Hawke government finally granted Hilaly permanent residency, after treasurer Paul Keating lobbied on his behalf.

"It was sheer populism," laments Chris Hurford. "Voting power got in the way of good policy."

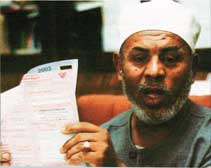

The affair would be ancient history, except that many Jewish leaders feel Hilaly repeated his sin recently, just as the memories of 1988 were fading. In the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, the Carr government had persuaded the Jewish community to join Hilaly in a call for community harmony. Stephen Rothman of the Jewish Board of Deputies overrode the objections of many Jews, believing it would be symbolically important for Hilaly to repudiate terrorism. So Rothman was chagrined to pick up a newspaper earlier this year and read a report which claimed that Hilaly, while preaching at a Lebanese mosque in January, had praised both suicide bombers and the September 11 terrorist attacks on the US. Even the Melbourne imam Sheik Fehmi Naji publicly criticised Hilaly and suggested AF1C reconsider his Mufti title.

So did Sheik Hilaly really say the destruction of the World Trade Centre was "God's work against oppressors"? Well, yes - and then again, maybe not. That widely used quote came from a transcript of Hilaly's sermon prepared by the Australian consulate in Lebanon, but the consulate's translation appears to be wrong in several key passages. According to an independent translation commissioned by GOOD WEEKEND, Hilaly did not boast of having four wives (he has only one), nor did he explicitly praise suicide bombers. What he did do, however, is recite a long poem about a young Arab boy farewelling his mother as he goes out to become a martyr to jihad; he also recited another long poem which suggested the planes that attacked the US were guided by God, and that one of the blessings of the destruction might be an Islamic awakening in the US and Australia.

Hilaly says the martyrs lie was referring to are the stone-throwing youths of Palestine, and that the September 11 passage simply evoked the mystery of God's actions. Isn't that just a little ambiguous? "It can certainly be viewed as ambiguous," he replies evenly,

So did Sheik Hilaly really say the destruction of the World Trade Centre was "God's work against oppressors"?

Well, yes - and then again, maybe not.

"especially if someone wants to take it out of context ... But if someone wants to look at the whole service, they would he able to look at it without ambiguity." And anyway, adds the Mufti, compared to the sermons that are usually heard in a mosque near the Israeli border, his was tame.

"especially if someone wants to take it out of context ... But if someone wants to look at the whole service, they would he able to look at it without ambiguity." And anyway, adds the Mufti, compared to the sermons that are usually heard in a mosque near the Israeli border, his was tame.

GOOD WEEKEND'S translator was unequivocal. "It is quite obvious," he said, 'that Hilaly looks at what happened on September 11 as 'God's work against oppressors'." But just to compound the confusion, a third translation prepared for SBS News backed Hilaly's version.

Clearly, Hilaly's pronouncements tan mean many things to many people. On this occasion, there were sufficient doubts to defuse calls for his resignation, and AFIC politely refused Hilaly's offer to resign. Sheik l-'ehmi says he's now satisfied that the original reports were inaccurate and his relationship with 1 Hilaly is once again cordial. The Mufti had escaped again through a hairline crack of ambiguity.

ON A WINTER'S MORNING, I ACCOMPANY Hilaly as he makes his weekly appearance addressing a group of Muslim women in Auburn. Women are among Hilaly's biggest supporters -- he helped establish the Muslim Women Association not long after his arrival in Sydney, and visitors to his office have been shocked to see female constituents drop in unannounced for advice on intimate aspects of marriage and Koranic scripture. Today he is in his element: the women sit on the floor around the edge of the room, heads swathed in scarves, while Hilaly occupies a chair before them extemporising on the correct techniques to deal with errant sons and bullheaded spouses.

It's a surprisingly lively gathering, with the women calling out comments and laughing as Hilaly hams it up: he imitates an angry husband by strutting like a rooster, demonstrates the ephemeral nature of material possessions by throwing his mobile phone across the room and advises them against finding a husband on the internet ("you'll give birth to a CD"). A few weeks later, he works the same charm on Sydney's Catholic Archbishop, Cardinal George Pell, at an interfaith gathering not far away. After one of Pell's usual lugubrious speeches, Hilaly digresses from his prepared notes to suggest that Catholics and Muslims promote harmony by forming a rugby team to take on the Carr government, with Cardinal Pell as captain. The room cracks up.

But charm has its limits, and the ground has shifted under Hilaly's feet in recent years. There is now a whole generation of Australian-born Muslims looking for a more progressive, homegrown leader, while at the other extreme are the young firebrands of radical Islam, seeking a more militant vision in the aftermath of the Iraq war. In the middle ground are many veterans of the Muslim community who privately admit they have lost faith in Hilaly's ability to unite their community.

For many, the breaking point came five years ago when Hilaly was arrested in Egypt and jailed on a charge of attempting to smuggle antiquities out of the country. Egyptian police claimed Hilaly paid his accomplices more than $200,000, and that one of their investigators had been murdered; it was only after Hilaly spent two months in jail that an appeals court cleared him. Some of his supporters suggested he was a victim of a vendetta by Egyptian authorities because of his radical past, while others claimed he'd been dragged unwittingly into a business dispute involving a friend's son. Now Hilaly acknowledges a new wrinkle in the story - he was involved at the time in a major property deal in Nasr City.

The plan, he says, was for a newly built "village" to be created in Nasr so expatriate Egyptians could revisit their homeland from Australia. Plans were drawn up by Sydney developers and Hilaly helped them secure land from the Egyptian government, but the deal went sour. "The project drowned," says Hilaly, "and the person supporting the idea - that's me - nearly drowned with it."

How this all morphed into charges of smuggling is unclear, but word of the Egyptian venture has seeped out, fuelling speculation that the Mufti is not the humble man of the cloth he appears to be. Hilaly scoffs at rumours that he derives money from a halal-meat business, saying he would "resign in one hour" if that were true. But another rumour, that he has an apartment in Cairo, turns out to be correct. "Of course," he shrugs. "Where would people expect me to stay?" Hilaly says he bought the place before coming to Australia and uses it whenever he visits Cairo.

The Egyptian debacle has emboldened Hilaly's opponents, as shown by the mob that attacked him outside Malik Eahd High School on Christmas Eve 2000. The incident was sparked when an announcer at the Voice of Islam radio station, broadcasting from a studio inside the school, began denouncing Hilaly and AFIC on the evening of December 24. After finishing Ramadan prayers, Hilaly drove over to demand his right of reply, accompanied by AFIC official Hafez Malas. According to Malas, scores of young men from the Islamic Youth Movement turned up on foot and in a van and attacked the Mufti as he tried to beat a retreat.

"We were lucky to protect ourselves," says Malas. "It was very, very dangerous."

Since then, the ever-shifting alliances in Sydney's Muslim community have taken several new turns. One morning recently, Hilaly popped into Al Faisal College to visit Shafiq Abdullah Khan, a veteran Muslim community leader. The two men sipped coffee, swapped news from the Middle East and laughed like old friends - which is remarkable when you consider that Shafiq Khan lobbied to have the Mufti deported back in the 1980s, when Hilaly was criticising the Saudi royal family. Given their history of antipathy, there is much cynical speculation among the Mufti's detractors about whether he is back on the payroll of the Saudi government.

At the Lakemba mosque, meanwhile, Sheik Yahya Safi is now the official representative of the Mufti of Lebanon, and he and Hilaly have offices on opposite sides of the mosque. The Lebanese Muslim Association insists the arrangement is amicable and helps Hilaly with his workload, although privately there's talk of a power struggle at the mosque. At the same time, a younger imam, Sheik Shadi Suleiman, is drawing crowds of young men with sermons that fiercely repudiate the temptations of Sydney streetlife. And up the road, in a prayer room above Lakemba shopping centre, Sheik Zoud conducts his meetings with Islamic Youth Movement members and continues his plans to buy the Belmore mosque. Asked if these neighbouring imams are rivals, Hilaly offers a typically opaque reply. "Actually, envy and conflict is an ongoing law of nature," he says with a shrug. "... [ But as long as I am here, we will not allow any extremists to have status in this mosque." Hilaly says he wants all the imams to sign a joint statement opposing terrorism, and was heartened when Sheik Zoud publicly repudiated Osama bin Laden and the September 11 attacks. So Hilaly's hot-and-cold attitude to Zoud - denouncing him one week, giving him money for his mosque thenext - may reflect the tricky internal politics of their relationship.

Outside the mosque, a man muttered a litany of allegations against Hilaly. "The man is not what he seems," he warned darkly. "His hands are not clean..."

In the end, perhaps Hilaly's maddening contradictions reflect the contortions of trying to serve so many conflicting constituencies at once. While keeping open his lines to the police, the Carr government and the intelligence services, he must simultaneously placate a Muslim community angry over its portrayal in the media and deeply divided by events in the Middle East. For the moment, none of his rivals surpasses him in either popularity or theological knowledge. But the imam is 63 years old and his heart condition means he sometimes sleeps with an oxygen bottle by his bedside. The void created by his exit may create a drama to rival anything that occurred during his reign.

ON A RECENT MORNING AT THE LAKEMBA MOSQUE, the Mufti's world was its usual whirling maelstrom of the bizarre and the humdrum. Hilaly was at his desk stamping marriage certificates with an Arabic seal, then getting called away to conduct a funeral ceremony. Suddenly the mother of Bilal Skaf, Sydney's most notorious pack-rapist, arrived on the doorstep demanding to know whether it was true that the NSW government was paying the Mufti to keep quiet about her son's situation. Outside the mosque, meanwhile, a young man in a knitted woollen cap pulled this reporter aside and muttered a litany of outlandish allegations against Hilaly. "The man is not what he seems," he warned darkly. "His hands are not clean..." Hilaly moves through all this with the kind of outward serenity that perhaps only the true believer can evince. Despite all that he has been through, he professes no plans for retirement. But when he does hang up his robes, a long family tradition will end -his father, grandfather and five generations of Hilarys before them were all Koranic scholars, he says, but the Mufti's Australian-born son, Mohammed, is opting for a more modern career path. The police force is one option, and there is also marketing, that ultimate expression of Western consumerism. Would Hilaly have preferred his son to follow the spiritual path of his forebears?

"After all the problems 1 went through, no," he says.

"I do not wish that fate upon my son."

"especially if someone wants to take it out of context ... But if someone wants to look at the whole service, they would he able to look at it without ambiguity." And anyway, adds the Mufti, compared to the sermons that are usually heard in a mosque near the Israeli border, his was tame.

"especially if someone wants to take it out of context ... But if someone wants to look at the whole service, they would he able to look at it without ambiguity." And anyway, adds the Mufti, compared to the sermons that are usually heard in a mosque near the Israeli border, his was tame.